IS POTS AN AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE?

Big news this week in POTS research! Researchers from the University of Oklahoma and Vanderbilt University have identified evidence of adrenergic receptor autoantibodies in a small group of POTS patients, suggesting that POTS may be an autoimmune condition in these patients. The study was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA). JAHA is an official journal of the American Heart Association, so this is great news for POTS awareness!

To help patients better understand what this means, Dr. David Kem from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center has kindly provided Dysautonomia International with a patient friendly explanation of this complex research. Before we get to Dr. Kem’s explanation, let’s go over the basics of adrenergic receptors and autoantibodies.

Adrenergic receptors are present on the surface of cells in many different parts of the body, including the heart, blood vessels, nerves, brain, lungs, bladder, gastrointestinal tract and elsewhere. There are two main types of adrenergic receptors in the body – alpha adrenergic receptors and beta adrenergic receptors. Within the alpha and beta types, there are many different subtypes (alpha-1, alpha-2A, alpha-2B, alpha-2C, beta-1, beta-2, etc.)

Think of adrenergic receptors like a TV antenna (if you are old enough to remember when TVs had antennas!). If the TV antenna picks up a signal, it transmits a message across the screen. In adrenergic receptors the “signals” are chemicals present in the body called catecholamines (primarily epinephrine and norepinephrine). The “message” is what the catecholamine tells the receptor to do. For example, constrict a blood vessel or make the heart beat faster.

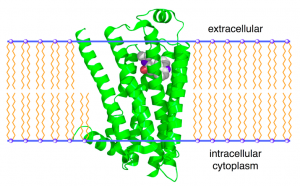

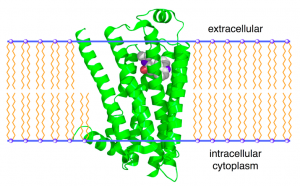

Image of an adrenergic receptor, which is stimulated by catecholamines.

Antibodies are proteins created by your own immune system to protect you from pathogens, like bacteria and viruses. The human immune system can make more than 1 trillion different antibodies, each one meant to protect us from a different pathogen. Unfortunately, sometimes the antibody formation process goes awry, and the antibodies created by your immune system can turn against your own cells. These trouble-making antibodies are called autoantibodies. Autoantibodies can attack, damage or interfere with the functioning of healthy tissues and cells in your body.

Now that we all know what adrenergic receptors and autoantibodies are, here is what Dr. Kem has to say about the adrenergic receptor autoantibodies recently found in POTS patients:

POTS occurs frequently, but not exclusively, in younger females and its onset is occasionally preceded by or associated with a viral-like illness. It is more than a minor annoyance for most patients and leads to significant life changes and limitations in normal life. Our present study (Autoimmune Basis for Postural Tachycardia Syndrome) has produced data supporting the idea that production of autoantibodies, circulating proteins that normally fight such infections, have instead interacted with critical site(s) on specialized cell membrane proteins which alter their normal cell function.

These autoantibodies interfere with the system which controls the ability of blood vessels to constrict, which is needed to prevent a drop of blood pressure as a person stands. In POTS patients, this inadequate response to standing leads to a generalized increase of activity in the body’s sympathetic nerve system, which frequently normalizes the blood pressure. This increased nerve activity, however, increases the heart rate which is a prominent symptom in POTS.

We have also discovered a second group of autoantibodies in some POTS patients which directly increase the heart rate.

The combination of these two autoantibodies appears to cause the abnormal heart rate response observed in all 14 POTS patients we have tested to date for these autoantibodies. We have previously identified similar autoantibodies in individuals diagnosed with idiopathic orthostatic hypotension (Editor’s note: see Agnostic Autoantobodies as Vasodilators in Orthostatic Hypotension: A New Mechanism and Autoantibody Activation of Beta-Adrenergic and Muscarinic Receptors Contributes to an “Autoimmune” Orthostatic Hypotension).

These autoantibodies may explain why beta blockers aren’t always effective in treating the tachycardia seen in POTS, since beta blockers fail to completely block autoantibody activity on their protein receptor and they fail to alter the partial blockade of the autoantibodies on the arteriole blood vessels that initiate the orthostatic problem.

Confirmation of our findings will require testing a larger group of POTS patients for these autoantibodies. We hope to eventually develop treatments to block these autoantibodies, without blocking the target receptor proteins at the cell surface at the same time. Such agents are in development and within a few years may be applicable in POTS. This approach may prove useful in several other diseases which are caused by similar autoantibodies.

Please note that Dr. Kem and the other researchers involved are not able to test patient blood samples for these autoantibodies outside of a research setting at this time. There are very strict federal laws that prohibit them from doing so. If such a test becomes available to the public, Dysautonomia International will be shouting it from the roof tops. Imagine that – a blood test to help diagnose POTS ? We’re looking forward to it, but there is much work to be done.

Dysautonomia International is committed to funding additional research in this area as quickly as possible. We are optimistic that this will lead to a better understanding of POTS, better ways to diagnose it, and most importantly, better ways to treat it.

If you would like to support the next phase of this exciting new research, please consider making a donation to Dysautonomia International today. You can make a difference in the lives of millions of people around the world living with POTS!

by

by

by

by

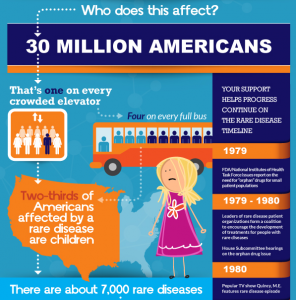

Dysautonomia International is pleased to partner with the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) to celebrate Rare Disease Day today. Did you know that overall, rare diseases are not that rare?

Dysautonomia International is pleased to partner with the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) to celebrate Rare Disease Day today. Did you know that overall, rare diseases are not that rare? fewer than 1 in 2000 individuals. Other countries have similar definitions.

fewer than 1 in 2000 individuals. Other countries have similar definitions.